The mod package is a lightweight module system; It

provides a simple way to structure program and data into modules for

programming and interactive use, without the formalities of R

packages.

This is a good question.

As units for code organization in R, packages are very robust. However, they are formal and compliated; they require additional knowledge to R and must be installed in the local library. Scripts, as widely understood, are simplistic and brittle, unsuitable for building tools and may conflict with each other.

Situated between packages and scripts, modules feature characteristics that are somewhat similar to those from other languages. They can be defined either inline with other codes or in a standalone file, and can be used in the user’s working environment, packages, or other modules.

Let’s see.

Install the development version from GitHub with:

devtools::install_github("iqis/mod")The mod package is designed to be used either attached

or unattached to your working environment.

If you wish to attach the package:

require(mod)

#> Loading required package: mod

#>

#> Attaching package: 'mod'

#> The following object is masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> dropmodule()/mod::ule()acquire()use()drop()provide()require()refer()Define an inline module:

my <- module({

a <- 1

b <- 2

f <- function(x, y) x + y

})The resulting module contains the variables defined within.

ls(my)

#> [1] "a" "b" "f"Subset the module.

my$a

#> [1] 1

my$b

#> [1] 2

my$f(my$a, my$b)

#> [1] 3Use the with() to spare qualification.

with(my,

f(a,b))

#> [1] 3Just like a package, a module can be attached to the search path.

use(my)The my module is attached to the search path as

“module:my”, before other attached packages.

search()

#> [1] ".GlobalEnv" "module:my" "package:mod"

#> [4] "package:stats" "package:graphics" "package:grDevices"

#> [7] "package:utils" "package:datasets" "package:methods"

#> [10] "Autoloads" "package:base"And you can use the variables inside directly, just like those from a package.

f(a,b)

#> [1] 3Detach the module from the search path when done, if desired.

drop("my")Use refer() to “import” variables from another

module.

ls(my)

#> [1] "a" "b" "f"

my_other<- module({

refer(my)

c <- 4

d <- 5

})

ls(my_other)

#> [1] "a" "b" "c" "d" "f"The mod::require() makes packages available for use in a

module.

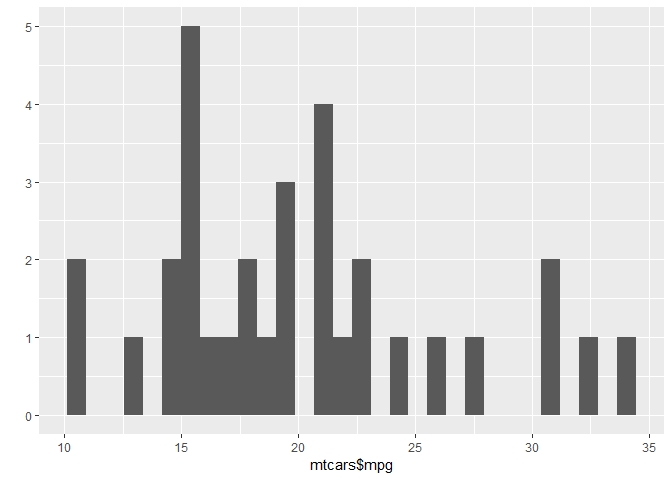

mpg_analysis <- module({

require(ggplot2)

plot <- qplot(mtcars$mpg)

})

#> Registered S3 methods overwritten by 'ggplot2':

#> method from

#> [.quosures rlang

#> c.quosures rlang

#> print.quosures rlang

mpg_analysis$plot

#> `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

Meanwhile, your working environment’s search path remain unaffected:

search()

#> [1] ".GlobalEnv" "package:mod" "package:stats"

#> [4] "package:graphics" "package:grDevices" "package:utils"

#> [7] "package:datasets" "package:methods" "Autoloads"

#> [10] "package:base""package:ggplot2" %in% search()

#> [1] FALSEA variable is private if its name starts with

...

room_101 <- module({

..diary <- "Dear Diary: I used SPSS today..."

get_diary <- function(){

..diary

}

})A private variable cannot be seen or touched. There is no way to

access the ..diary from the outside, except by a function

defined within the module. This can be useful if you want to shield some

information from the user or other programs.

ls(room_101)

#> [1] "get_diary"

room_101$..diary

#> NULL

room_101$get_diary()

#> [1] "Dear Diary: I used SPSS today..."Another way is using provide() function to declair

public variables, while all others become private.

room_102 <- module({

provide(open_info, get_classified)

open_info <- "I am a data scientist."

classified_info <- "I can't get the database driver to work."

get_classified <- function(){

classified_info

}

})

ls(room_102)

#> [1] "get_classified" "open_info"

room_102$open_info

#> [1] "I am a data scientist."

room_102$classified_info

#> NULL

room_102$get_classified()

#> [1] "I can't get the database driver to work."The below example simulates one essential behavior of an object in

Object-oriented Programming by manipulating the state of

..count.

counter <- module({

..count <- 0

add_one <- function(){

#Its necessary to use `<<-` operator, as ..count lives in the parent frame.

..count <<- ..count + 1

}

reset <- function(){

..count <<- 0

}

get_count <- function(){

..count

}

})A variable must be private to be mutable like

..count.

The following demonstration should be self-explanatory:

counter$get_count()

#> [1] 0

counter$add_one()

counter$add_one()

counter$get_count()

#> [1] 2

counter$reset()

counter$get_count()

#> [1] 0It is imperative that mod be only adopted in the

simplest cases. If full-featured OOP is desired, use R6.

A module is an environment. This means that every rule that applies to environments, such as copy-by-reference, applies to modules as well.

mode(my)

#> [1] "environment"

is.environment(my)

#> [1] TRUESome may wonder the choice of terms. Why refer() and

provide()? Further, why not import() and

export()? This is because we feel import() and

export() are used too commonly, in both R, and other

popular languages with varying meanings. The reticulate

package also uses import(). To avoid confusion, we decided

to introduce some synonyms. With analogous semantics, refer()

is borrowed from Clojure, while provide()

from Racket; Both languages are R’s close relatives.

If a module is locked, it is impossible to either change the value of a variable or add a new variable to a module. A private variable’s value can only be changed by a function defined within the module, as shown previously.

my$a <- 1

#> Error in my$a <- 1: cannot change value of locked binding for 'a'

my$new_var <- 1

#> Error in my$new_var <- 1: cannot add bindings to a locked environmentAs a general R rule, names that start with . define

hidden variables.

my_yet_another <- module({

.var <- "I'm hidden!"

})Hidden variables are not returned by ls(), unless

specified.

ls(my_yet_another)

#> character(0)

ls(my_yet_another, all.names = TRUE)

#> [1] ".var"Nonetheless, in a module, they are treated the same as public variables.

my_yet_another$.var

#> [1] "I'm hidden!"module_path <- system.file("misc/example_module.R", package = "mod")To load and assign to variable:

example_module <- acquire(module_path)

ls(example_module)

#> [1] "a" "d" "e"

example_module$a

#> [1] 1

example_module$d()

#> [1] 6

example_module$e(100)

#> [1] 106To load and attach to search path:

use(module_path)

ls("module:example_module")

#> [1] "a" "d" "e"

a

#> [1] 1

d()

#> [1] 6

e(100)

#> [1] 106It could be confusing how modules and packages live together. To clarify:

require()use()refer()Depends on mod

packageAs aforementioned, the package is designed to be usable both attached and unattached.

If you use the package unattached, you must always qualify the

variable name with ::, such as mod::ule(), a

shorthand for mod::module(). However, while inside a

module, the mod package is always available, so you do not

need to use ::. Note that in the following example,

provide() inside the module expression is unqualified.

See:

detach("package:mod")

my_mind <- mod::ule({

provide(good_thought)

good_thought <- "I love working on this package!"

bad_thought <- "I worry that no one will appreciate it."

})

mod::use(my_mind)

good_thought

#> [1] "I love working on this package!"